I’ll just come out and say this: sign-up forms must die. In the introduction to this book I described the process of stumbling upon or being recommended to a web service. You arrive eager to dive in and start engaging and what’s the first thing that greets you? A form.

We can do better. In fact, I believe we can get people engaged with digital services in a way that tells them how such services work and why they should care enough to use them. I also believe we can do this without explicitly making them fill out a sign-up form as a first step.

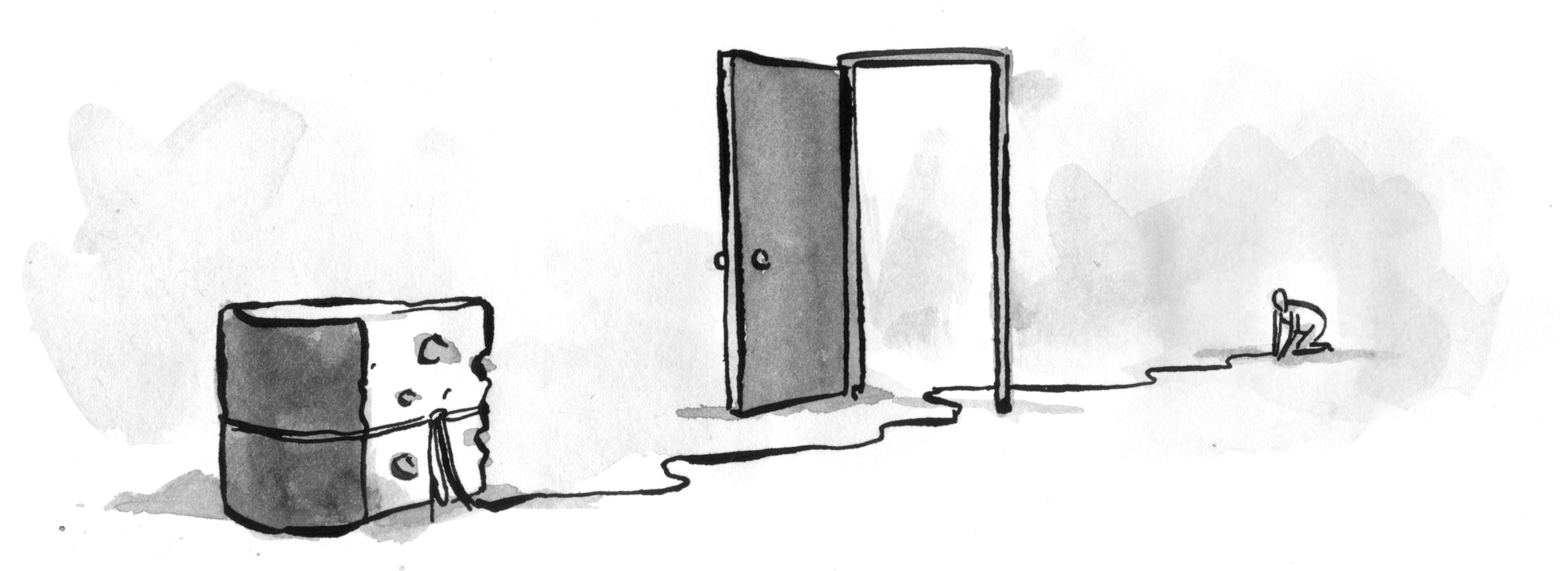

But before we get into the potential of gradual engagement (your path out of sign-in “dullery”), let’s look at how the process of engaging with an online service typically works. Since 2007 was a breakout year for online video, it’s safe to assume a lot of people went on the web to post one of their videos. Perhaps they heard Google Video was a good place to do so. Upon arriving at the site, they found a link to share their video and what happened next? They got the form in Figure 13.1.

Figure 13.1

A sign-up form greets new customers at Google Video.

You are required to give us your email address, select a password, tell us your name, your location, verify this strange word, agree to our terms of service, and finally, you will get what’s behind the form.

Now contrast this approach with that of another online video service: Jumpcut. The primary calls to action on the Jumpcut front page, as seen in Figure 13.2, are Make a Movie and Try a Demo. Right out the gate, Jumpcut is interested in telling you how their service works and why it’s great for you. So let’s dive in.

Selecting Make a Movie brings up a single input field for the title of your movie and a few options you can use to upload media files for your movie. Selecting Upload from this list allows you to add images, audio, and video from your desktop computer. Once you do, you are put in Jumpcut’s web-based video editor. Here you can edit your movie, add styles, coordinate your audio, video, images, and more.

Figure 13.2

The process of adding a video to Jumpcut introduces you to the services the site provides, namely online video editing.

So far, no form. It’s only when you want to publish or share your movie that Jumpcut asks for your name and email so you and others can access the movie you just made. Through this process, you learned what Jumpcut does, and you did it without having to jump through a sign-up form. That’s gradual engagement.

Let’s look at another example. Geni is a web service that allows anyone to set up a family tree and share it with family and friends. What’s the first thing potential customers need to do when they arrive at Geni? Fill out a registration form? Nope, they make a family tree. After all, that’s what’s Geni is for.

The front page of Geni (Figure 13.3) makes it clear what the site is for. So get started creating a family tree by entering your name and email address. Next, you can add your parents, their siblings, or your siblings, and in no time, you have a pretty good family tree going. While you were at it, Geni sent you an email with your user name and password so you can get back to your family tree anytime you want.

Figure 13.3

Geni’s process of creating a family tree contains no explicit registration forms and gets people acquainted with Geni’s service right away.

Once again through the process of gradual engagement, you learned what a web service does, and you did it without an explicit registration form requiring you to fork over a lot of information. In Geni’s case, their approach to gradual engagement has given them five million profiles in five months. Not too shabby.

It’s worth noting that any web service that automatically sets up an account for its customers may leave some people confused about whether they actually have an account or not. After all, they did not explicitly create one. As a result, these services need to ensure they have an easy way for people to access their account information if they did not see or chose to ignore the email they were sent outlining their account information.

Another example of gradual engagement comes from TripIt: a web service that allows people to assemble a trip itinerary, complete with weather and driving directions, using only their flight, hotel, and rental car confirmation emails. The first step to getting started is emailing TripIt a confirmation email from upcoming or past travel. TripIt will send you back a note that provides access to an automatically created personal travel itinerary (see Figure 13.4).

Figure 13.4

Using TripIt starts by forwarding a travel confirmation email—not with a sign-up form.

Once again, your first step in using TripIt is not a sign-up form. Instead, you learn how the service works by actually using it. TripIt gets your name and email address from the confirmation emails you send the service. From there, if you want to edit your name, email, or create a password to access the site, you can do so. Chances are you will do so now that you know how the service works and how it benefits you.

When exploring if gradual engagement might be right for your web service, it’s important to consider how a series of interactions can explain how potential customers can use your service and why they should care. Gradual engagement isn’t well served by simply distributing each of your sign-up form input fields onto separate web pages.

While I applaud Fidelity’s myplan form (Figure 13.5) for its attempt at making financial planning more enjoyable, I’m not sure distributing each of their input fields to separate web pages and presenting them as slider inputs is the best way to achieve their goal of getting people to understand what Fidelity can do for them.

Best Practices#section2

- When planning a customer’s initial experience for your web service, think about how you can avoid sign-up forms in favor of gradual engagement.

- If you do opt for a gradual engagement solution, ensure that it gives potential customers an understanding of how they can use your service and why they should care.

- If you choose to auto-generate accounts for potential customers, ensure there is a clear way for them to access their account. Chances are that people will either ignore or not see account creation emails, and may be uncertain if they have an account or not.

- Avoid gradual engagement solutions that simply distribute the various input fields in a sign-up form across multiple pages. It’s a good possibility that this will reduce efficiency and not delight anyone.

It is indeed a nice article and clearly demonstrates the bugging issue of Signup forms. But it misses some issues –

1.)A better approach to kill signup forms is OPENID. This article has not mentioned it at all.

2.)Second thing is, when I tried to comment on this article, I was served a “Create an account ” form first and then comment later. I think Alistapart.com should itself try to implement

what has been said in this article.

Nilesh, I disagree with the practice of using OpenID for anything other than a blog – so I don’t think it is really relevant in this article. Centralizing our information and consolidating it may make things seem simple or easy, but really what is your identity on the internet? If we hold all this info in one place, it could be compromised more easily and used against use in a more horrific way. This scares me because it is like giving out an ID card – something a person shouldn’t need on the internet but I fear it will happen soon anyways.

I agree with the idea of this article though. It is annoying to have to give up so much of your info just to see how something works. I would like to apply this in some of the projects I have in my future.

This seems like a great idea, but collecting personal data without age verification (13+) is illegal in the US. Also, having played with geni a little bit, quite a few people have felt like they’ve been spammed, since there’s little indication that they’ve actually signed up for anything.

As folks continue to bring up OpenID, I’ll re-iterate: single sign on solutions also have the potential to remove the need for sign-up forms. However, they have yet to become widely adopted by the majority of Web users (hopefully this changes over time), and they only resolve the issue of user identification. Single Sign-on solutions don’t let people experience applications and services before requiring them to authenticate.

The point here is that the initial experience with a Web-based product can be used to engage new customers and illustrate what a service offers and how it works. User authentication doesn;t meet that goal.

Similarly, keeping sign-up forms short (while a very worthwhile pursuit) doesn’t address this point either. The fundamental problem is we have a tendency to treat people as record in a database. That’s what the sign-up form is: an output of the fields in a recordset that uniquely identify a user. This is not how people think of themselves and their relationship to product or service. So while we can make sign-up forms shorter and we can try to spread single-on sign solutions, the bottom line is we are concerned first with the recordset, and second with the person coming to our site or service.

I genuinely feel there is an opportunity to do better.

@John Josef and others:

With respect, I think you need to understand more about OpenID before you accuse it of “centralising” information. OpenID is a decentralised identity system, which is why I and many others use it. I did not, and never would, use a single sign on system for anything other than a closed network for precisely the reasons you state.

that signing up for things stinks in the long run. Just now I signed up to post on this site, and I had to fill out another form. Some of the information you give is for demographics, and others are just plan stupid. I was going to sign up for an AOL account and they asked me to supply my phone # and address. I stopped right there because I know that if I finished who knows what kind of stuff I would get in the mail from AOL.

I wanted to comment this, and after attempting I actually had to sign up. Hahahaha. I was going to say, I’ve seen sites lately where I don’t need to sign up, but it asks for just my name and a link. I would prefer all sites like that.

Great excerpt, great discussion – I look forward to reading Luke’s book. My comment is, as Jeffrey Zeldman pointed out earlier, slightly off-topic as it relates to commenting/posting rather than testing out web services, but since the registration issue keeps coming up, I thought I’d toss this in to the discussion.

I am currently doing some ad hoc research around the effects of registration on the volume and relative value of user-generated content. I agree with others here that the inclusion of a minor registration barrier should elevate and enrich the discussion – at least that’s always been my hunch – but I was recently referred to the following article that suggests that registration actually dilutes quality discourse:

http://blog.topix.com/archives/000106.html

Has anyone else here witnessed the phenomenon described here, where the absence of a registration barrier actually generates more and higher quality responses from users? If this is true, then the only benefit of the registration barrier benefits the business (potentially less spam to comb through).

The vast majority of premium content sites that allow commenting and voting ask for, at minimum, a registration via email address and a password before users can submit content. But does the fact that everyone’s doing so make it a best practice? We strive in all other ways to reduce the amount of administrative debris we present to users, but in this case we seem to agree that it’s worthwhile to derail them from the completion of their task.

bq. _Registering before you can comment helps encourage a higher level of conversation and discourage (although not eliminate) spam. For these reasons, such registration has become best practice and industry standard on sites that allow readers to post comments._

Although a common, I wouldn’t call it best practice. This doesn’t bring any value to the users who just want to post one comment, it can even discourage from posting. The way this site does it is to make users enter a username and password, but without requiring an email address for confirmation. This doesn’t stop spam, and doesn’t stop multiple registrations, so why not just let users comment directly, and only require to enter a “type this word” function (with an image showing scrambled letters) to prevent bot automatic posting?

The Doodle website (www.doodle.ch) is even better – there is no registration or login.

(BugMeNot doesn’t either! And I’m not Peter Brown)

i think it,s a great post.

Hi,

Excellent post. But how could you ever sign up to a new GMail account without providing any data? I think sign up forms will still exist even in 20 years…

Reading some of the comments on here about “ooh… it was an article about signup forms and we had to signup to comment, how ironic / ALA get your house in order…” etc… strewth!

Ok, as an occasional reader of ALA articles (usually from a google link – I long-since learned to trust ALA articles) I just decided that it was about time I signed up, so I can take part in the discussions. I was required to enter a username, password, and my name. Email and URL were optional but I gave them anyway. Bish-bash-bosh and I’m signed in. It’s not like they are asking for my biometrics! A few simple fields filled in and we are good to go.

Furthermore, surely the ALA process is exactly what this article was about? You get to read some excellent articles on a wide range of subjects. You get to read the comments that people make. If you want to comment, you are informed that you will need to sign up. The sign up process is simple and doesn’t even require email address. By reading “you need to sign up to post comments” you know exactly what benefit you will get from signing up. From reading articles and comments, you know exactly what you are signing up for. Seems to me that ALA have got it bang on with this!

The other thing, as I said I am an occasional reader of ALA. Now that I have taken the next step and signed up, this has introduced a new level of my relationship with ALA, which means I may be more of a regular than before – with increased benefits for myself and (hopefully!) ALA.

I was just about to comment on this myself.

The entire point of the article was to let the people that come to your site actually see what they get out of membership and then have an “information as needed” sign-up form. ALA is a perfect example of this.

On the other hand, there are cases where there must be a sign up form for something to work right. Timo points out a good example with webmail, something that does actually need a sign up before you get to use it, but still there should be something like screenshots and maybe a video of some actual use with a dummy account that people can see before deciding to sign up for an account.

The key is balance, letting users get as much of a taste of your service as you can before you actually need to have them sign up to avoid things like malicious use of your service. You also need to balance what you ask for, a webmail company does not need my name, age, address, social security number, height, weight, age, birthplace, first pets name, and a contract to give them my firstborn child, etc… It needs Name, ID, PW, and maybe an alternative form of contact (snail mail or phone number) in case you forget your PW and need to reset it. Let me do a job search without being a member of your site though, and if I like your search methods I’ll join, rather than force me to join before I even see a readable screenshot of your search page.

I see this as useful methodology in my direct marketing work. I market to potential new medical plan customers for my Medicare clients. Standard method is to mail them an info kit and drive them to our micro-site to answer a short questionnaire, check a box to ask for an outbound quote call, etc. or ask for sign-up forms. Medicare is scary, and I see this as a way to make it warmer to the prospect (age 64+, in terms of Web familiarity and comfort). Seems like it could only lessen the rate of abandonment in those sign-up forms.

I read this article and found what it had to say rang true in a number of cases. However, there are sites where the details of a member need to be checked before access is given. One way to check that is to get the information required in a sign-up form. the account is created but not validated until the site moderator can check the validity of the applicant.

This is a different area to ‘web services’ this is really very specialist, data sensitive web communities. Ensuring the quality of members before they gain full access goes some way towards protecting existing members. It also improves the quality of experience once they have registered – opening doors to new content and new features. Whilst providing good content and useful experience for those who do not wish to register. I admit this is not perfect but for some sites it is essential.

The one thing I found disturbing about this article was the blanket approach it advocates – all sign up forms must die. this is not true and not wise.

The most annoying thing in a sign up form is mostly the capture. Sometimes the letters or numbers are so weird deformed that it is not possible to read them. And if you enter the wrong code and the form is reloaded sometimes all the entries you have done before are deleted. These captures really must die!

I will admit I am completely of a mind with you on gradual engagement – and you will see this approach in our ecommerce experience at Seatwave… (wait for it) …but:

– why don’t you publish numbers? I am constantly bewildered by aspiring thought leaders propensity to expatiate an opinion without providing numerical evidence of why it matters, for example:

Did Google’s signup process have a higher conversion rate to singup or did the other website’s? Your opinion’s nice and fine, of course…

I will state categorically that 100% of businesses that succeed pay attention to numbers – and 100% of those that don’t (well, ok 99%) completely fail.

Jeffrey — I definitely take your point about desiring a higher order of discussion on ALA, but OpenID might actually encourage that at this point — since it would make it a lot easier for those of us with OpenIDs to get in and focus on the comment we’re thinking of making before having to register.

I guess my point is that they’re not mutually exclusive. You can still offer registration as you already do, but for those with IDs stored elsewhere, you can make it easier for us to get up a running — and to prove that we’re from a certain URL/web address.

Jeffrey — I definitely take your point about desiring a higher order of discussion on ALA, but OpenID might actually encourage that at this point — since it would make it a lot easier for those of us with OpenIDs to get in and focus on the comment we’re thinking of making before having to register.

I guess my point is that they’re not mutually exclusive. You can still offer registration as you already do, but for those with IDs stored elsewhere, you can make it easier for us to get up a running — and to prove that we’re from a certain URL/web address.

Good info with clear examples.

Only a few visitors will ever register on a website.

We are now discussing how to make our “Free Trial” as simple as possble. We need some basic info: email, url, username.

But can we ask more? Like company name, real name, country.

As mentionned, OpenID should be an option avoiding to register on our website. OpenID will get more traction as he organisation is getting into marketing thigs now.

Agree 100% with most of the article, however, using Fidelity MyPlan as an example shows that the author did not take the time to understand what it actually does. In the case of MyPlan it’s not a sign up form, but a way to collect some basic info in order to proceed. Without that info MyPlan simply cannot be used and since you can’t have a talking computer ask users a few of these basic questions that was the most fun, visual way they could have done it.

I thought the article was very informative.

It really showed me some things that I need to keep in mind when consulting with clients.

This is a very good article. I strongly agree with the author. This is a big help when I interact with business clients. Thanks for this wonderful tip! Keep it up!

Cool article, I agree with the author as sign up and sign in processes are boring! I can point you to another site (http://www.webyam.com) that allows you use its services without sign up and sign in!!

I came across this post after seeing it referenced on another site adactio.com (1) The most elegant sign up form I have seen so far doesn’t look like a form…rather a simple fill in the blanks. Very non threatening, concise and quick.

Any doubts were disnmissed about the effectiveness of this form when I asked an 83 yr old Grandmother to sign up. Not a single question nor problem.

It’s found at http://huffduffer.com/signup/

G. Wayne Clayton -Social Marketing Expert

(1) http://adactio.com/journal/1521/

The website examples used in this article were for free online services. I don’t like sign up forms either and would like to get straight to the point….but does not having a sign up form apply to services that cost money? (say, a monthly price) Would this confuse and “trick” potential customers into thinking that there is no cost..until we asked for them to pay a couple hundred bucks after they’ve gone in, used our product, and is ready to share with the world?

Hi everyone,

I’d like to make a comment on one of the earlier statements.

Rochelle is asking a very good question about how to deal with using fewer forms in the case of paid services.

In my opinion, a big part of the internet business community is already moving towards making more and more free material available to their customers to generate trust and demonstrate both quality and concern toward them.

So far, the only remaining “price” for users is the signup form, which, indeed, seems like the bare minimum in the case of a paid service oriented website.

But ultimately, isn’t it conceivable to deliver the same free material without even asking prospects for an email?

1- If the material is really good, prospects will come back for more and then it’s only fair to request that they give some information, which is necessary anyway since they require a paid service and become actual customers.

2- wouldn’t such a system attract even more potential buyers?

“Honest Reviews”:http://www.HonestFreeReviews.com

This article is about what this comment function is not about?

– Why do I have to sign up to comment an article?

– Why can´t I start writing before i sign up, like the article says?

– When I have signed up I have to find my way back to the article I wanted to comment?

– But on the other hand, what I wanted to say is that I would be frustrated with thw video service who says “create your movie” and the wants me to register before I can use it (ie publish it). It didn´t say “create movie and sign up”. But now I have put in effort and time to make this movie and are left with the choice of throwing my work away or give them my details and more time…

Bad idea.