We’ve all seen arguments in the design community that dismiss the role of beauty in visual interfaces, insisting that good designers base their choices strictly on matters of branding or basic design principles. Lost in these discussions is an understanding of the powerful role aesthetics play in shaping how we come to know, feel, and respond.

Consider how designers “skin” an information architect’s wireframes. Or how the term “eye candy” suggests that visual design is inessential. Our language constrains visual design to mere styling and separates aesthetics and usability, as if they are distinct considerations. Yet, if we shift the conversation away from graphical elements and instead focus on aesthetics, or “the science of how things are known via the senses,” we learn that this distinction between how something looks and how it works is somewhat artificial.

Why aesthetics?#section2

For starters, aesthetics is concerned with anything that appeals to the senses—not just what we see, but what we hear, smell, taste, and feel. In short, how we perceive and interpret the world. As user experience professionals, we must consider every stimulus that might influence interactions.

Perhaps more importantly, “aesthetics examines our affective domain response to an object or phenomenon” (according to Wikipedia). In other words, aesthetics is not just about the artistic merit of web buttons or other visual effects, but about how people respond to these elements. Our question becomes: how do aesthetic design choices influence understanding and emotions, and how do understanding and emotions influence behavior?

Aesthetics and cognition#section3

Cognition is “the process of knowing.” Based on patterns and experiences, we learn how to understand the world around us: What happens if I push that? What does this color suggest? Cognitive science studies how people know things and aesthetics plays a critical role in cognitive processing. In the example below, which one of these is clearly a button? And why?

Here, aesthetics communicates function. The example on the right resembles a physical button. The beveled edges and gradient shading remove any doubt about its function. In this case, these are characteristics of affordance, which are aspects of design that help a user to discover how they might interact with an object. Translation: if it looks like a button, it must be a button.

Similarly, there’s a reason good confirmation screens have a check mark and are likely to involve some shade of green: Green is good. Red is bad. Yellow is something to think about. When designing, we must consider how our brain interprets the meaning of color, shadow, and shading. We rarely notice these aesthetic choices, except when people get them wrong:

In this example, the visual language confi‚icts with the intent of the message.

What we are discussing here is how our brain interprets the meaning of things such as color, shadow, shading, and other natural occurrences. Just pick up a piece of paper and watch how the shadow changes as you bring the page closer to you. It’s these kinds of natural occurrences our brains observe every day in the real world. When we use these cues on a screen, they carry with them the same real world properties.

But, there’s more to aesthetics than just communicating function, and more to styling than mere enjoyment.

Aesthetics and affect#section4

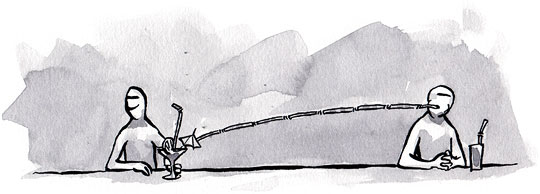

When we talk about “affect,” we’re talking about feelings and emotions—not about the “I feel positive about your brand” sense of feelings and emotions, but about the ways in which they influence perceived and actual usability. Let’s revisit our button example, with a slight change:

Cognitively speaking, both of these are obviously buttons. Neither button is “wrong” as in our previous example. However, research into attention, persuasion, choice, happiness, learning, and other similar topics suggests that the more attractive button is likely to be more usable by most people. To get an idea of where this perspective might come from, consider this comment on emotions from neurobiologist Antonio Damasio:

“…emotion is not a luxury: it is an expression of basic mechanisms of life regulation developed in evolution, and is indispensable for survival. It plays a critical role in virtually all aspects of learning, reasoning, and creativity. Somewhat surprisingly, it may play a role in the construction of consciousness.” [1]

In many design conversations, there is a belief that applications are made enjoyable because we make them easy to use and efficient (interestingly, whether it’s stated or not, these conversations value the role that aesthetics plays in cognition). However, when we talk about how emotions influence interactions, it’s closer to the truth to say things that are enjoyable will be easy to use and efficient. Allow me to explain.

You remind me of…#section5

Product personality influences our perceptions. Think about how quickly we form expectations about someone simply based on how they dress or present themselves. This is something the automobile industry has known for years, as they spend money to create products that express a specific personality people might identify with. Why does a Dodge Ram seem more durable? What makes a Mini Cooper seem zippy and fun? While there are certainly performance features to support these mental claims, we can also see these attributes expressed in the car’s form.

Similarly, the UI design decisions we make affect the perceived personality of our applications. In the example below, which window is friendlier? Which one looks more professional?

Products have a personality. Why should we care? Consider this:

- People identify with (or avoid) certain personalities.

- Trust is related to personality.

- Perception and expectations are linked with personality.

- Consumers “choose” products that are an extension of themselves.

- We treat sufficiently advanced technology as though it were human.

…and so on.

By making intentional, conscious decisions about the personality of your product, you can shape positive or negative responses. Take a look at Sony and how they applied this knowledge in the Sony AIBO. Let’s consider why they made this robot resemble a puppy.

Here, you have a robotic device that isn’t perfect. It won’t understand most of what you say. It may or may not follow the commands it does understand. And it doesn’t really do all that much.

If this robot was an adult butler that responded to only half our requests and frequently did something other than what we asked, we’d consider it broken and useless. But as a puppy, we find its behaviors “cute.” Puppies aren’t known for following directions. And when the robot puppy does succeed, we are delighted. “Look, it rolled over!” What a great way to enter the robotics market.

Consider: What kind of personality are you creating with your application? And what expectations does this personality bring with it?

Can you trust me on this?#section6

According to a 2002 study, the “appeal of the overall visual design of a site, including layout, typography, font size, and color schemes,” is the number one factor we use to evaluate a website’s credibility.

This makes sense. Think about how our personal appearance (our personal aesthetic) affects how people perceive us; or how product packaging infi‚uences our perception of the product inside.

Below is a gas pump near my house. Contrast that with the station shown on the right.

I’ve stopped filling up at the gas station on the left, even though it’s closer to where I live. Why? This kind of maintenance (or lack of maintenance) leaves me unwilling to trust them with my credit card information. Clearly, appearance does affect trust.

So, how do we create trust in our application interfaces, aside from providing the basics, such as reliable information and uptime? By being attentive to visual design, for one thing. Attention to design details implies that the same care and attention has been spent on the other (less visible) parts of the product—which implies that this is a trustworthy product.

I’ve seen many great design comps get butchered during development. Things such as inconsistent fonts, odd padding, line-heights, and over-compressed images plagued the final release. While this may never come out during functional testing, how might these sloppy UI details affect perceptions of your product?

Put it all together and…#section7

Why should we really care about perceptions? Consider these findings from research presented at CHI 2007:

“…users judge the relevancy of identical search results from different search engines based on the brand…Participants in the study indicated that the results from Google and Yahoo were superior to identical results found through Windows Live or a generic search engine.”

What is a brand but perceptions? In this study, functionally identical results were perceived as better due to brand attributes such as trust, personality, and perception. What’s rational about that?

Hold that thought.

Attractive things work better#section8

Okay, so maybe perceptions are important to product design. But what about “real” usability concerns such as lower task completion times or fewer difficulties? Do attractive products actually work better? This idea was tested in a study conducted in 1995 (and then again in 1997). Donald Norman describes it in detail in his book Emotional Design.

Researchers in Japan setup two ATMs, “identical in function, the number of buttons, and how they worked.” The only difference was that one machine’s buttons and screens were arranged more attractively than the other. In both Japan and Israel (where this study was repeated) researchers observed that subjects encountered fewer difficulties with the more attractive machine. The attractive machine actually worked better.

So now we’re left with this question: why did the more attractive but otherwise identical ATM perform better?

Norman offers an explanation, citing evolutionary biology and what we know about how our brains work. Basically, when we are relaxed, our brains are more fi‚exible and more likely to find workarounds to difficult problems. In contrast, when we are frustrated and tense, our brains get a sort of tunnel vision where we only see the problem in front of us. How many times, in a fit of frustration, have you tried the same thing over and over again, hoping it would somehow work the seventeenth time around?

Another explanation: We want those things we find pleasing to succeed. We’re more tolerant of problems with things that we find attractive.

Stitching it all together#section9

Recent studies into emotions are finding that we can’t actually separate cognition from affect. Separate studies in economics and in neuroscience are proving that:

“affect, which is inexplicably linked to attitudes, expectations and motivations, plays a significant role in the cognition of product interaction…the perception that affect and cognition are independent, separate information processing systems is flawed.” [2]

In other words, how we “think” cannot be separated from how we “feel.”

This raises some interesting questions—especially in the area of decision making. In short, our rational choices aren’t so rational. From studies on choice to first impressions, neuroscience is exploring how the brain works—and it’s kind of scary. We’re not nearly as in charge of our decisions as we’d like to believe.

Consider what you’re doing with your interfaces to speak to people’s emotions? Industrial product design, automobile manufacturing and other more mature industries get this—with tools such as Kano modeling that have been used for decades. But user interface development is still maturing and catching up to what these other disciplines already know: the most direct way to influence a decision or perception is through the emotions.

So, is “pretty design” important?#section10

When we think about application design and development, how do you think of visual design? Is it a skin, that adds some value—a layer on top of the core functionality? Or is this beauty something more?

In the early 1900s, “form follows function” became the mantra of modern architecture. Frank Lloyd Wright changed this phrase to “form and function should be one, joined in a spiritual union,” using nature as the best example of this integration.

The more we learn about people, and how our brains process information, the more we learn the truth of that phrase: form and function aren’t separate items. If we believe that style somehow exists independent of functionality, that we can treat aesthetics and function as two separate pieces, then we ignore the evidence that beauty is much more than decoration. Our brains can’t help but agree.

Reference#section11

[1] Emotion and Feelings: A Neurobiological Perspective by Ant³nio Dam¡sio

[2] “Emotion as a Cognitive Artifact and the Design Implications for Products That are Perceived As Pleasurable” by Frank Spillers

@Helen I have not thought about this and come up with an answer– to be honest, I’m usually the one being reminded by my team about these accessability issues! Ticks and crosses, icons, etc. can reinforce the message being communicated with color choices. Shapes, as well– I’m thinking about the “STOP” signs at the end of each section of a standardized SAT test (these reference driving associations). Also, things like type choice or even all caps can convey a lot of meaning. Of course, cultural context would have to be considered in these discussions. I hadn’t though about white labeled versions of Google and trust– good comment!

@Mads You are exactly right! Context is a critical (overarching) consideration for all decisions– aesthetic or otherwise. Have you seen “my thoughts”:http://twurl.cc/tqm on the subject? There is ongoing debate about a “universal aesthetic” vs “subjective aesthetics,” (I won’t go there!) but your point is also about how context governs our response to a certain aesthetic. I’m so glad you mentioned this! The “trashy looking pump encountered on a dusty desert drive” would be part of a good narrative experience. My context for the gas station is a fairly well-off suburb where this kind of inattention sends a terrible message! To be clear, my goal for writing this is simply to legitimize the consideration of aesthetics for a set of reasons not usually addressed– I’d hope these considerations would be filtered through an awareness of context and the overall experience! As far as predictability goes, that’s a tricky one, as I’m sure you know. In some contexts, we don’t want things to change; however, as humans we also thrive on novelty, surprise, serendipity, etc. Though as you point out, designing for these things can be quite tricky.

@A.J. Yes, thank you for clarifying the title for me! Also, you wrote that “_aesthetic design best-practices should be integrated into the wireframing stage_” — Yes! Yes! Yes! As far as the A/B testing goes, I wish more designers participated in these practices– seeing metrics from a _well-constructed_ test can be quite eye opening, and also the shortest route from “I think I know what works” or “this is what I like” to “here is what works.” This “ALA article”:http://www.alistapart.com/articles/designcancripple/ is a great one of the subject.

@Chris You wrote: “_…it’s not a matter of one side winning over the other, it’s a matter of balancing the two. The goal is that the sum of the form and the function is greater than each separately._” I’m glad you add this. I’ll clarify even more– sometimes it’s a _balance_, sometimes it’s a _tradeoff_, other times it’s a _prioritization_. The key, as you indicate, is to be clear about the objective/end goals that a project is supposed to accomplish, and then make decisions accordingly. My goal in writing this article was to present a “rational” argument legitimizing the functional value of aesthetics, especially where there is heavy interaction (software applications for example). As I allude to in the opening sentence, I’ve seen way too many conversations defending or dismissing aesthetics for the _wrong_ reasons. In writing this, I hope to deepen that conversation, and provide a framework by which to understand the different viewpoints on the value of design. If there is to be arm wrestling over design choices, I hope that folks (on either side) are arm wrestling over the relevant merits of aesthetics. Since entering the field of UX design more than a decade ago, I witnessed the constant tension between usability engineers, development teams, designers (“at all levels of maturity”:http://www.bplusd.org/2005/10/19/a-rough-design-maturity-model/ ), business folks, marketing groups… Each has something quite valuable to add to the equation. But, it’s frustrating when we don’t value each group’s contributions or understand how to orchestrate these different interests to work together to create value for business and value for customers.

You also write: “_there’s a myriad of interpersonal and psychological factors that impact a project…_“ My experiences in both design and strategy roles has been leading me more and more into the realms of psychology, neuroscience, social sciences and other “human” focused disciplines. My most “recent presentation on Seductive Interactions”:http://www.poetpainter.com/thoughts/article/the-art-and-science-of-seductive-interactions is an example of where this focus is leading me.

@Michael Thanks! Added to my reading list.

Pretty nice article, but as some readers point out, when it comes to web design is not that easy as it seems, at least not when the designer in charge has no clue about how back ends work, or how a “simple” layout change can complicate things more than required, or how to work together with developers, web is not the same as magazines!

As you probably have guessed by now, I’m a programmer, but coming from a musical training before, I’m inclined to see thru the details, in this case visual details, and enjoy doing design work too, not only code stuff, so most of the time I notice when some design needs more work, or it’s overworked… and this is my daily scenario:

The boss (senior designer) wanders around and sees an unfinished website on a comp screen, probably an online game if it’s my computer, and starts with the round of suggestions… “that button could look better if you do it like this”, “why don’t you move that box over there”, “I told you I don’t want to display the score in this screen”, “make that ship to jump instead of slide”, or even worst: “hey, let me do it”, etc. you can imagine the rest :), all pointless if he stop for a second to remember it is UNFINISHED work!.

For quite a long time, every time he did that to me we followed up with a tiresome discussion, ending with the lousy argument “well, I’m your boss so do as I say”… even if there is no reason other than him used to go with his rather limited taste on design and me finishing a less than stellar job… sadly.

Now I know better so I stop him right away by telling, “hey, I’m not finished here, I’ll tell you when it’s done and then you can change stuff as you please, remember, design it’s easier to change and make it fit than possibly hundreds of lines of code just because this particular thing is in the wrong place”, then I can go on and finish the job with the design included and having a lot less requests for changes than if I let him do his thing as usual 🙂

What’s the point you probably are asking yourself, simple answer:

Visual stuff it’s kind of easier to understand for everybody, or it should, but when it comes to user interaction is not just about “hey, this looks amazing”, it should work amazing too.

And you’ll find amazing design and development working together when you actually don’t notice it, and the less you notice, more work is behind… certain brand with a fruit logo comes to mind 😉

While the bulk of the design advice that says usability doesn’t have to be sacrificed in favor of eye-candy, I disagree with the general tone of the article; the opposite notion, that usability usually makes eye-candy take the back seat.

I wrote a more indepth post on my blog:

http://noscope.com/journal/2009/04/in-defense-of-good-design

Great observations stephen. Aesthetics and usability go together. I always believed that along with usability, aesthetics also plays a vital role in a products acceptance from the uers.

What a beautifully written piece! Powerful, convincing… and you do it without coming off like a design zealot. I agree with pretty much everything you say, but for the design crowd I guess this is preaching to choir.

I’ve worked in the tech world (like Oracle) on both sides, and it’s not that left-brained folks like ugly interfaces. But that (like you mentioned in a comment), it’s a matter of trade-off/prioritization. Making a business case (with research, etc.) for the extra $/time for design will help.

My favorite quote regarding beauty is from R. Buckminster Fuller, who said:

When I am working on a problem, I never think about beauty but when I have finished, if the solution is not beautiful, I know it is wrong.

Look at a modern printed page against a typewritten page of 25 years ago or a sloppy handwritten page. Which is the most beautiful? Which accomplishes its goal best? It is the same with all things.

I agree with everything you said. It’s difficult, but designers really do need to strike a balance between functionality and attractiveness. Just having one without the other is enough to turn users off, and I don’t envy the designers who have to work very hard to have both components work in harmony. However, the designers who are able to find that balance will be rewarded with happy clients and respect from their peers.

The best way for me to illustrate what I’m thinking is to give you examples up front, and go from there:

Abraham Lincoln, John F. Kennedy, Theodore Roosevelt, Jimmy Carter, Richard Nixon.

The one thing they all have in common was that they had very distinctive personalities that alienated a lot of people, and carried them to war, assassination, career failure, or a combination.

“The boring presidents.”

The one thing they all have in common is that they all became president. Also note that there’s lots more of them than there are of the flamboyant type.

Do you want to take the flamboyant gamble? Are you willing to pay the high price, if you’re one of the lucky few that succeeds?

There many benefits to being utilitarian. Google vs. Microsoft Live is the best example of that in the web sphere. In 100 years, Google might be forgotten as “boring”, but Microsoft rocked the boat so intensely that it’ll be a historical highlight for centuries. Who could forget Bill Gates and the computer revolution? On the other hand, is it so bad to be Google?

I mean, if your goal is to make money, is it better to do it the Microsoft way, or the Google way? Which personality is most likely to be avoided, as the article mentions?

How much is too much? If it’s not relevant to what the user wants then it’s just wasted space. It seems some designers just add “eye candy” to take up space. Almost like they are just looking for more things to add. Nothing beats a well laid out, easy to follow design with an easy navigation. You have about 15 seconds for users to find what they are looking for and having to troll though too much eye candy (which a lot of it slows the page down), then they are gone to the next.

Hurrah! Recognizing that emotion is an inseparable and integral part of decision making is far better than trying to set things up on logic and structure alone. This applies to selling a car, arguing a case in court, and designing a web page.

In each case the end goal is different. And in each case, you can get by on low costs, facts and figures, or navigation structures, respectfully, but they will only get you so far. To consistently reach the goal (making a sale, winning a case, or letting a person complete their task), the emotional components must be factored in, or you risk getting derailed. (Although admittedly, in every case emotion isn’t always applied with the best intentions for the “end user”.)

The context of the decision and the goal to be reached will determine how deeply the emotional side can be addressed along with other factors: i.e. you usually don’t want much discussion about feelings when getting people out of a burning building. It’s a continuum of applicability, not an all-or-nothing situation. Sometimes emotional aspects of a subject or design will be highlighted front-and-center, sometimes more subtly addressed, or sometimes fall behind more pressing elements. Yet the consideration for how emotions will play in reaching the goal must be there somewhere.

Addressing emotion _alongside_ cognition, rather than ignoring it or putting on a separate shelf, will help you get through shaky ground and see new opportunities for both yourself as the designer and those using your website.

Thanks for the article, Stephen.

Ya, I agree with that early comment about Nielsen’s site. It’s really terrible to look at. My HTML mentor (i.e., he that introduces me to the web) is of the same mind as Nielsen. They seem to think that if the information is useful and relatively easy to access, then why waste time making it look pretty. Well, making it look pretty makes it even easier to use, as the author of this article has argued quite well. I look at Nielsen’s site, or my mentor’s and am dumbfounded. I just don’t know what to do with the site. I’m glad that this author could put into perspective my feelings when I visit not-so-pretty sites.

This is one of the best article’s ive ever read. It’s so hard trying to explain to some clients why they should pay for “good looking design.” Most of them just don’t get it.

I will definitely be using this article as reference for our clients.

I’d love to see more articles on this subject. Does anyone know of any similar?

Great write up. I think the citing of evolutionary biology alone drives the point home.

bq. “We want those things we ï¬nd pleasing to succeed. We’re more tolerant of problems with things that we ï¬nd attractive.”

This is true in all things where perception plays a role. And since perception effects every aspect of our lives, it is always a factor. A man, unhappy with his wife’s ability to communicate or emphasize with him is more inclined to accept these flaws if say, dinner is made regularly, or if he finds her physical appearance, stunning.

As humans we both rightfully and wrongfully place our trust in things we find visually pleasing. Although in a tangible world, repeated use will eventually expose flaws. Online, would these exposed flaws not also seise to be tolerated. Where, a better option is sometimes a few clicks or a search query away.

Although this article, is filled with great sources and examples to defend the experience layer we as designers and developers have another responsibility. To not neglect the underlying process that we are _dressing up_. A flaw is a flaw, an inaccessible interface is still inaccessible. It’s about the difference between user experience and user satisfaction. In many cases these are one in the same, but relying too heavily on aesthetics alone will still result in a negative perception. Somewhere down the line.

Excellent article.

Every designer, developer and business person should read and embrace this. Knowing and understanding this will give anyone selling a design, application, product, whatever great “selling points”.

I was just having a discussion about this last night. Graphic designers sometimes get caught designing for their own inner circle trends rather than what the hoi polloi who will be visiting a site look for. I recently read an article that lambasted bevels, shading, and drop shadows as frivolous, yet when I showed examples much like your button example to NON-DESIGNERS, the choice was overwhelming.

Hi, thanks. This is a good article, and quite ad hoc to what we are doing now. Some months ago I got this Dilbert cartoon that talks about this topic:

http://andres.jaimes.net/2009/03/07/is-beauty-better-than-functional/

Thanks again…

@ Oliver “Our world is 3D — cluttered — structured — textured — colourful — shadowed — foggy — dusty.”

I love that Oliver! I think what a good web designer does is take all these aspects of reality and package them in a neat and structured way that upholds the content.

When people see something online that looks real, i think it sparks interest! People are more likely to PLAY with things and stare at them if they have a polished and unique look. And that’s a good foot in the door for any website!

You have put a lot of efforts to write such wonderful article and it is been pleasure reading thorough it.