No. One word, a complete sentence. We all learned to say it around our first birthday, so why do we have such a hard time saying it now when it comes to our work?

Guilt. Fear. Pressure. Doubt. As we grow up, we begin to learn that not doing what others expect of us can lead to all sorts of negative consequences. It becomes easier to concede to their demands than to stand up for ourselves and for what is right.

Need to no#section2

As a user experience designer, I have made a career out of having to say No. It is my job to put an end to bad design practices within an organization before I can make any progress on improving the lives of our customers. And it’s rarely easy.

My client says, “I want to build a spaceship!” I say, “No, we need to make a kite.”

My client says, “We need to keep that space blank for my next genius idea!” I say, “No, we’ll find space for your idea once you have one.”

My client says, “I want this done tomorrow!” I say, “No, it will take a month.”

I am a human brake pad.

Each one of us brings an area of specialization to our projects, and it is our responsibility to exhibit that expertise. If you don’t know anything that no one else on your team knows, then it’s probably time to walk away. But if you do, it is your duty to assert that capability and share your knowledge for the betterment of the final product.

Mahatma Gandhi said, “A ‘no’ uttered from deepest conviction is better and greater than a ‘yes’ merely uttered to please, or what is worse, to avoid trouble.” As people who create stuff with the hope that other people will use it, it is outright cowardly for us to protect ourselves before defending the needs of our users.

When to no#section3

When I’m incredibly passionate about something, I tend to be stubborn. And when I recognize a problem, I’m not one to keep it inside. As a result, I have had some situations with teammates and clients in which I have been rather abrasive with my delivery of a no. Fearful that I won’t be heard or understood, I have overemphasized my position to the point that people don’t hear what I said but how how I said it.

Having been made aware of this issue and given the opportunity to fix it, I can freely admit now that it was getting in the way of my ultimate goal—helping people. As practitioners in design and development, there are many common difficult situations in which we may find ourselves, and there are tactful ways to handle them. Perhaps you will recognize a few of the following.

Citing best practices#section4

When you’re hired to serve a specific function on your team but are asked to do something you’re not comfortable with, often the best way to say no is to simply educate the other on best practices.

Kelly Andrews, owner of 1618design, recently received a client request to remove a quick e-mail-only mailing list signup from their site in favor of a full-page signup form.

Fearing that this would significantly decrease their number of subscribers, Andrews informed them that it is common practice for websites to include a quick subscribe since most people don’t want to spend the time filling out a form. A simple but powerful business case: The shorter option “would allow for immediate capture of interested people,” he explained. And they were sold. They hadn’t considered that before, but once they had that information, it armed them with the power to make a better choice. “The client was happy with the decision,” Andrews said. “She thanked me for being an expert and educating her instead of just doing what was asked.”

Data reigns#section5

When Samantha LeVan worked as a user experience designer at Corel, she was surrounded by a large team of engineers who were also accustomed to doing design. Most of the time, they had really interesting ideas that LeVan enjoyed riffing off of, but now and then they got stuck in the details and LeVan would have to make her case.

In one particular design, one of the engineers insisted that a drop-down component was necessary for the selection of three options. LeVan urged that three radio buttons would be more appropriate, but the engineer was unconvinced. The disagreement went on for a few days before LeVan realized that she needed data to support her case.

She turned to the CogTool—a UI prototyping tool that automatically evaluates the effectiveness of a design based on a “predictive human performance model”—developed at Carnegie Mellon University. The results showed that expert use task time was dramatically reduced with radio buttons over drop-downs. Seeing the facts, the engineer relented.

“Your opinion won’t matter,” says LeVan. “It’s important that you prove your point with numbers.”

Pricing yourself out#section6

Sometimes the best way to say no to bad design is not to take on the project in the first place. When Charlene Jaszewski, a freelance content strategist, was recently asked to help a friend’s brother with a website for his concrete company, she knew he had a limited budget but expected that she could help him limit the scope.

“Besides wanting ‘flying’ menus on each and every page, in a different style for each page,” Jaszewski recounts, “he wanted huge orange diamonds for the menus on the front page, and to top it off, he wanted a custom-made animation of a concrete truck on the front page and in the sidebar of every other page—the barrel rolling around with the logo of his company.” Now that just gives me shivers.

Jaszewski advised that his customers would be more interested in some relevant content, such as a portfolio of his previous work, but he was convinced that he needed lots of flashy extras to impress his visitors. And he wouldn’t give up.

Not wanting to overtly turn down the work, Jaszewski contacted animators and Flash designers, and came back with a price that was five times the business owner’s budget. He demanded a lower price, but Jaszewski just apologized and said that that’s what she would have to pay the appropriate people to do the work. Unsurprisingly, he took a pass, and Jaszewski later found out that he’d been trying to get his dream site built for the past eight years. Happily, she wouldn’t be the one to give it to him.

Shifting focus from what to who#section7

In April 2009, Lynne Polischuik, an independent user experience designer, was hired by an early stage startup—a private photo-sharing web app—to act as project manager to get them to launch. The product was intended to be an alternative to Facebook for parents who desired private groups of friends with whom to safely share photos of their young children.

Because the team envisioned the product as appealing to all members of the family, they wanted people of all ages to be able to use the app—including children and elderly grandparents without e-mail addresses. To allow for this, they developed a login system that relied extensively on cookies and technological trickery to provide secure access without requiring the user to enter credentials. Things were constantly breaking, and as a result, no one could log in.

Polischuik felt she had to step in. “I ended up making the argument that they needed to design not for extreme edge cases, but for the more probable, and revenue generating, ones,” she explains. “Would someone who doesn’t have an e-mail address be savvy enough to want to share images and photos on the web? Probably not.”

To sway the team, Polischuik took a step back and did some user research to develop personas to guide their decisions. Once the team was refocused on who they were really designing for, they were able to move forward more strategically. As disagreements in execution came up along the way, she would do a few quick usability tests of the proposed idea, and let the team see with their own eyes how their prospective customers struggled. By reframing the argument away from their opinions and demonstrating the negative impact on the user, the opposition was quickly defeated.

How to no#section8

Last October while on the phone with Harry Max—a pioneer in the field of Information Architecture, co-founder of Virtual Vineyards/Wine.com, (the first secure shopping system on the web), and now an executive coach—I complained about having way too much on my plate and desperately needing someone to give me a break.

He made me realize that it was actually I who was to blame, taking on more than I could handle by not protecting my time, and recommended that I read The Power of a Positive No by William Ury.

The book changed my life.

Ury proposes a methodology for saying no “while getting to Yes.” He argues that our desire to say no is not to be contradictory, but rather to stand up for a deeper yes—what we believe to be true, right, virtuous, and necessary. And that instead of making our defense a negative one, we can frame it in a positive light that is more likely to lead to a favorable outcome.

The following may sound really corny, but bear with me. It has completely transformed how I handle conflict and decision-making.

The structure of a positive no is a “Yes! No. Yes? statement.” In Ury’s words: The first Yes! expresses your interest; the No asserts your power; and the second Yes? furthers your relationship. For example, you might say “I, too, want prospective customers to see our company as current and approachable, but I don’t feel that a dozen social media badges at the top of the page will help us achieve that. What if we came up with a few alternative approaches and chose the most effective one together?”

He advocates not for just delivering your no in that manner, but also preparing for it and following through on it in the same way. Without a plan and without continued action, your assertion is a lot less believable—and a lot less likely to work.

Some of the most powerful takeaways from the book just might help you when it comes time for you to fight the good fight.

- Never say no immediately. Don’t react in the heat of the moment, or you might say something you don’t really mean. Things are rarely as urgent as we believe them to be, so take a step back, go to your quiet place, and really think through the issue at hand. Not only will your argument be clearer once you’ve had a chance to rehearse it, but it’s more likely the other will be ready to hear it.

- Be specific in describing your interests. When saying no, it’s better to describe what you’re for rather than what you’re against. Instead of just maintaining a position, help the other person to understand why you are concerned and what you’re trying to protect. You may just find that you share the same goal, and can work together to find the right solution.

- Have a plan B. There will be times that other people just won’t take your no for an answer. So you’re going to need a plan B as a last resort. Are you going to go over the person’s head? Are you going to prevent the project from moving forward? Are you going to quit? By exploring what you’re truly prepared to do ahead of time, you’ll have considerably more confidence to stand your ground and you won’t be afraid of what might come next.

- Express your need without neediness. Desperation is never attractive and won’t get you anywhere. Present your case with conviction and matter-of-factness. Does your assertion cease to be true if the other person refuses to agree? No. So don’t act like it does. Needing the other to comply makes you look unsure and dependent, diminishing yourself and putting them in a position of power.

- Present the facts and let the other draw their own conclusions. I’d venture to guess that most of the time you’re working with people who are pretty smart, pretty logical, and pretty well-intentioned. Perhaps they just don’t have all of the information that you do. Instead of telling them what to think, it is more useful to provide the necessary facts on which they can base their own judgment. Sometimes allowing the other person to feel like the decision was partially their own will help you get your way.

- The shorter it is, the stronger it is. Pascal famously said, “I wrote you a long letter because I didn’t have time to make it shorter.” The longer the argument, the sloppier and less well-thought out it appears. You don’t need five reasons why something won’t work; just one good one will do.

- As you close one door, open another. Don’t be a wet blanket. If you strongly believe that something shouldn’t be done, devise an alternative that the team can get behind. You aren’t helping anyone—let alone yourself—if you simply derail the project with your objections. Being a team player instead of a contrarian will help build trust and respect for your ideas.

- Be polite. Ninety-nine times out of 100 we’re talking about issues of mild discomfort and dissatisfaction of our users, not life-or-death issues. There’s no reason to raise your voice, use inappropriate language, or cut anyone down. When you do, you prevent people from hearing the essence of what you’re trying to communicate. So keep your cool, be kind, and give your teammates and clients the respect they deserve. Just because you might understand something that they don’t doesn’t mean you’re a better person than they are.

Good to no#section9

By taking pride in your work and upholding your role on a team, you will help to create a positive environment for all involved. No doubt other people will follow in your footsteps, and each person will become more responsible for themselves and for the greater good of the project. You’ll be seen as more professional, more authoritative, and more reliable.

Also consider the possibility that you may be steamrolling over other people’s ideas, and they’re too afraid to speak up. One of my favorite sayings is: “God gave us two ears and one mouth to use in proportion.” Let this be a reminder not only to say no, but to be willing to hear no, and to encourage others to do the same.

As I can understand, the main sence of this article is somehow similar to the meaning of “assertiveness”:http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Assertiveness .

I hope you liked my title.

It’s a very well written article. I agree and understand where a lot of the opinions are coming from. I think I work in an environment where “no” is totally discouraged and the corporate mentality over rules any creative input. It’s sad but that’s job security for you. I think a lot of it has to do with people hearing “Yes mam and yes sir” so much they forget how to respond to “no.” However, I do use “no” a lot on my freelance work (after hours). It feels good.

I especially liked the bullets: “Present the facts and let the other draw their own conclusions.” and “As you close one door, open another.” I try to have a solution for anything I turn down or disagree with to keep things moving. Presenting the facts is a huge part of that.

Thank you for the article, I enjoyed it and I’m glad someone out there has the power to use the word a lot.

I’m an in-house designer, so my surroundings are a bit more corporate than freelancers or agencies. However, from my very first interview I was told that “‘No,’ is an acceptable answer.'” This has stuck with me, and it’s very evident here that those who live by that and respond positively to that move up and grow within the company.

Great principle to live by, and some very solid fundamentals for applying to achieve positive results. Thanks Whitney!

This is an important topic, Not only for successful project management but career management as well.

As “designers,” we tend to focus on problems and solutions while ignoring the problem of selling our solutions. This often happens within the minefield of corporate politics. As communication experts, it’s important to craft an effective, personable style that transcends politics. Always be prepared to make your case with logic, data and precedent. Delivered with sincerity, conviction sells.

I routinely practice many of these strategies — pricing myself out, leading others to their own conclusion, etc. — Sometimes it doesn’t work out, but more often than not it leads to successful projects and relationships that will enhance your career.

Great topic. Great article. Thanks – db

Thank you for this article. I’ve recently come into my own in saying ‘no’ – forced to learn by client situations.

I think it is as valuable to give yourself permission to say no as much as anything else. If you can remove yourself from the pressure and dependency that you talked about, it allows decision making, and ultimately the work you do, to be much better.

Doing excellent things often requires a ‘no’ to less excellent things.

Thanks again.

Thank you for this article. I’ve recently come into my own in saying ‘no’ – forced to learn by client situations.

I think it is as valuable to give yourself permission to say no as much as anything else. If you can remove yourself from the pressure and dependency that you talked about, it allows decision making, and ultimately the work you do, to be much better.

Doing excellent things often requires a ‘no’ to less excellent things.

Thanks again.

Great article, really like the bit about not treating people as dumb just becuase they dont understand you.

You might want to read “How to lose friends and infuriate people”

Excellent article. After many years in the design field I have learnt to say no, because I want to provide the best solution (which may not always be what the client asked for). The client will always thank you in the end, but it does mean you have to have the courage of your conviction. That takes experience.

It’s as much about questioning assumptions as anything else. I like the quote about listening and speaking in proportion. You have to listen, ask questions, and be open minded. Reminds me of another favourite quote: “The mind is like a parachute. It only functions when it’s open”.

If I were to write the article myself, I would probably not have put it this nicely, though I share the exact same thoughts. Great job. Thanks for this.

Ravi Balla

I’ve had quite a number of time-wasting enquiries recently. I think the economic downturn has driven a few hopeless cases into thinking they can launch any old business idea and make a fortune! These people often come in wanting something that is either going to end up costing me money in wasted time or drag down the standards of the work we output.

Luckily, I can tell these a mile off now and often employ the high pricing model (so at least if they do say yes then it will be worth it!), or bashing out a fast outline quote to get a sense if they are interested first. Better that, than wasting hours on a full blown proposal only for them to drop off the face of the earth.

I’d gotten into the bad habit of clicking to ALA articles, lightly skimming through them, and then moving on to what I thought were more pressing things.

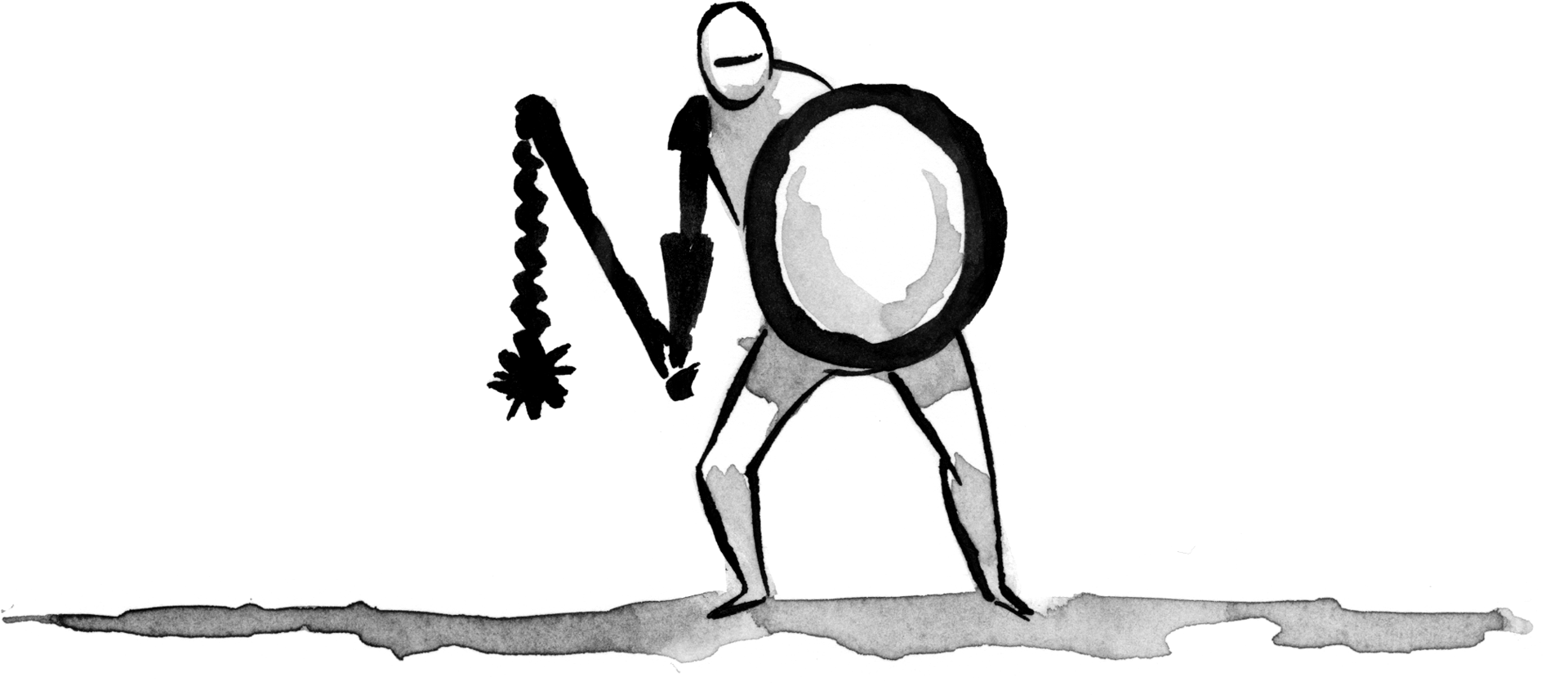

With this latest issue I was determined to break that pattern and was rewarded tenfold by reading this article, full of fantastic examples and useful links. Really, really good stuff–including Kevin Cornell’s illustration, which I would suggest should be turned into some sort of case study for illustrations.

Kevin Cornell’s illustrations are often examples of perfection in what illustration should do; extend the meaning of an article, away from the literalness and act as a counterpoint to the main proposition. This NO is one more time a marvel of precision. Bravo for the article, text and image.

Thanks for a great read (and I also liked your post about this article on your blog). I’ve used the Yes! No. Yes? approach and it works well.

Whitney, I’ve only just discovered you and I think you’re a genius. “No” is my favorite word, but your tips and explanations make everything so much more palatable. And CogTool?! Where has that been all my life?! I’m going to use it TONIGHT to test some options so I can make some points in a meeting this week!! Thank you!

It is such hard work (re-) learning how to say no. This article could easily apply to so many aspects of life at large. Great job.

I’m so glad you enjoyed the article, and yes, CogTool is amazing! It was developed by Bonnie John, the former head of the Master of Human Computer Interaction program at Carnegie Mellon (my alma mater), and her fantastic team. It’s seen as an academic tool, not often used by practitioners, but I think it rocks.

I could not agree with you more. When I saw Kevin’s illustration for the first time (when this was published yesterday), I actually cried. He encapsulated my message so precisely, it was shockingly awesome.

So glad you slowed down with this one. Really thrilled that you felt it was worthy of your time. Thank you!

Yes, very witty comment subject! So glad you enjoyed the article, and the structure I presented it in. Now go make good use of it.

You are very fortunate to work in an organization that values No, and I’m guessing is a lot better off for it.

I hadn’t heard of that one before, I’ll definitely go check it out. Thanks!

Could just be the way this was written, but it’s interesting that the one field quick signup form was arbitrarily cited as best practice, which may not be the case depending on the client’s goals.

That situation should’ve been handled with “Data Reigns”.

What if there was a business case for getting more information? Maybe ease of segmentation and followup for better marketing and sales/lead conversion?

The true best practice in that situation is “let’s test it out and see what works best (based on your business goals)”.

I agree with the above commenter in that saying no takes practice. If you can, try saying no to subordinates first so you can gauge their reaction. Then you can move on to your Chief Exec…

I’ve never had a problem when it comes to saying ‘no’ regarding “web design”:http://www.machinwebdesign.co.uk. Furthermore clients I have worked with have often responded, well, positively to me saying it. I think when they hear a designer essentially saying “I dont want to do that – so much so that I dont want your money” it rings alarm bells with them – “It must be a bad idea if they don’t want the job”. Of course the designer back it up with constructive and supporting criticism else you risk just coming across as having a creative hissy fit.

I’d say it’s often the case that your input really is valid; however, it’s all in how you say it. If you can give them the whole picture view, then show how your point fits in, then you’ve given them the benefit of your input.

What they do with it after that is another question. They may be wrong; on the other hand, they may have some point that changes the whole scenario.

In either case, I’d say it’s not just all about being right, or validated as being right … it’s about doing the right thing.

I’m fairly new to freelancing, and have yet to build up the sort of reputation that clients will automatically listen to. There are a plethora of really good designers out there, some of them too geographically close for comfort (I’m looking at you, “Mark Boulton”:http://www.markboultondesign.com/ ). I’ve had both good clients (“you’re the expert”) and bad ones (“I don’t like that font, it looks too wimpy. Change it to Tahoma.”)

Saying no is a valuable skill that will protect the standard of work produced and reduce time spent catering to nightmare clients.

I’ve often found that oftentimes it is not about saying “yes” or “no” but instead being able to take a step back and reframe the problem. Clients may tend to focus on the solutions (e.g. I want that to be purple instead of black) and a simple “yes” will create a jumbled mess of an end product while a “no” will create an unhappy client. The approach has therefore been to take a step back and ask them what the problem is (e.g. the color black looks too morbid) and then let the experts like graphic design figure out the best solution.

Being in the design field myself i find this issue often. I find if you disagree with your clients change they do take your opinion onboard. At the end of the day they are paying you for your knowledge in design, you wouldnt change something on someone building you a plane would you?

My experience has been that analytics data is the easiest way to back up a “No.” For example, I knew this homepage we had designed (which has subsequently been jammed full of extraneous content over the course of a year) had SO many elements that weren’t getting clicked, but without proof we decided to allow the client free reign and wait before putting our collective foot down.

When it came time to apply new branding to the site, we used the overwhelming amount of unclicked links (supported by our analytics data) to say “No” to the huge laundry list of requests for the homepage. The best part was there was no argument, no battle of opinions or conflicting “I thinks”. It was all right there.

Great article on the importance of pushing back on clients. Also, I really enjoyed your talk at AEA Minneapolis.

I can tell within the first 20 seconds of the conversation if the project is a no go on my end. Saying no is a thousand times better than saying yes and having a client from hell with a project from hell.

As I looked for what would be my “must read” of the morning, I came across your article. (A ritual I recently began as part of my daily work day.)

Reading through the different case vignettes, it got me to thinking about when not saying No has caused issues for me in my business. I have no problems (or hesitation) saying No when a client requests a design or feature that is not in their best interests. However, where I do have problems with No is when schedules are discussed.

In general, I run about a 4-6 week start time from the point a contract is signed off and I can roll-up-my-sleeves and dig into the project. However, we all know that usually when a client reaches out to do a project they are ready to start RIGHT AWAY. That usually leads to “negotiating” time for both the start time and incremental milestones.

In good conscious, as days as trimmed here or there, I optimistically believe, “Yes. We can do this.” In reality, it usually doesn’t happen. In some cases, it turns out even the original schedule was overly optimistic. The end result is that the client is disappointed (in many cases), and worse, I am disappointed at myself for allowing it to happen.

As you point out in your article it IS hard to say no. We are conditioned to “get along” with each other. To make each other happy. To avoid distress.

In the end, we pay the price, even if it was conscientiously done with the best of intentions.

With that I need to sign off so that I can go work on the proposal that was due to a prospect two days ago, and the wireframes on two other projects that are past due. :-S

Over the early weeks in helping with/investing in a movie project, I spotted some serious flaws. In talking yesterday with the filmmakers and citing my concerns, inching toward my intention of removing myself from the film going forward, we had almost a group epiphany as I leveled with them. And then we came up with the glue that holds the film’s narrative arc together and gives it its marketing appeal.

It was the use of the Creative ‘No.’

Or put another way, saying “No” and giving good reasons why (plus possible alternatives), shows a client that you a) know what you’re talking about and b) really care about the success of their website.

I hear you on this. Sometimes out of fear of losing a gig, we say Yes to an unrealistic schedule. But the reality is that you’re doing both yourself and the client a major disservice in the long run. When you start is typically less critical than when you end, and being honest and realistic throughout the process will help ensure that you meet that final deadline. Ultimately it’s about setting expectations well, and then following through.

That’s a great example. “Group epiphanies” as you called them are created, not happened upon. By making the client a partner, and clearly defining the problem *together*, you can devise a solution together. Making them feel like they were a part of the decision making process is really the ultimate goal. Nice work!

I can appreciate you wanting to dissect the case study, since that’s something I’d probably do, too. I had to limit the full story to just a few words, so I’m gonna ask you to trust that this was a situation in which citing best practices were most appropriate. I’m sure we’ve all faced a similar scenario.

Couldn’t agree with you more! Oh how I wish I trusted my gut more in the past. Getting much better at it now.

I heard this in the movie Troy “Imagine a King fighting his own battles? wouldn’t that be a sight” said by Brad Pitt before he fights against the Australian giant Nathan Jones with one swing of his sword.

Amen to that! Its not the kings who win battles and wars, its their men. If you are serving a King like Agamemnon you better take a step back or even fleet back! There is no honor in fighting for someone who is not worthy of fighting for!

Thanks for sharing Whitney. It is refreshing to hear someone that explains things so eloquently. I was able to say No to 3 ideas this week alone that left me holding a profit where I would have had a loss if I had said yes.

Your advice is fantastic, and I am sure that you will be hired for many jobs that you may not even conceive right now

You’re awesome!

Sam