A few years ago, Joe Clark famously wrote the following:

If your site has valid code or something trivially close to same, you are working with, and within, Web standards.

If you serve up tag soup or any document with myriad validation errors, you are merely using CSS layout….The matter is now settled.

Almost exactly one year later, Doug Bowman had a different take (emphasis mine):

We don’t point out validation errors on public redesigns anymore. We know a valid site is such a tiny part of any overall measure of success. Validation is something I only do on my own work now.

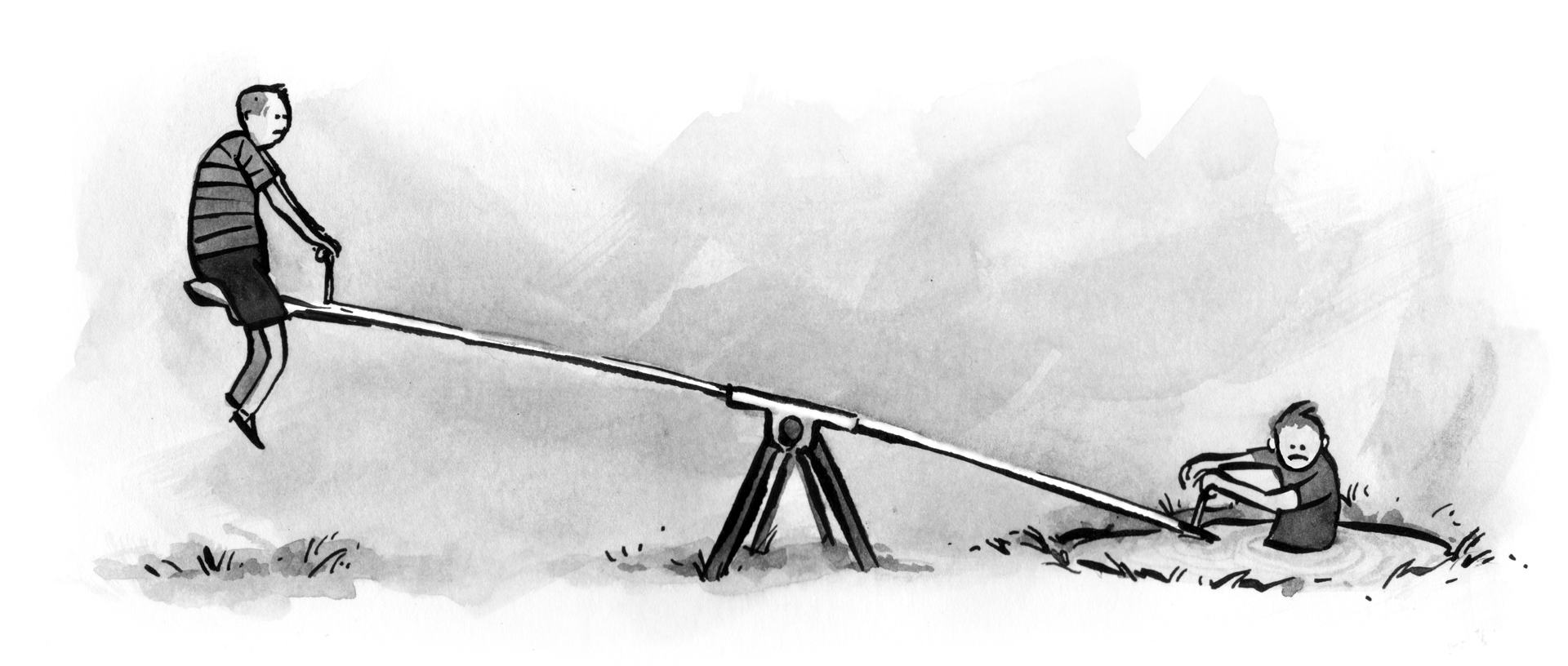

Here we have two well-known standardistas, both of whom have done (and will do) more for the adoption of standards than this author ever will. Yet both have different takes on what role validation plays in designing for the web. In fact, they perfectly represent the division that exists between standards advocates today. You probably find yourself taking one of two positions on validation:

- You take a hardline stance, rightly stating that if we fail to follow the conventions of a language, then we’ve produced something altogether different and, well, invalid.

- You take a pragmatic view, rightly stating that the invalid code generated by broken tools and third-party code shouldn’t negate one’s overall commitment to web standards.

So if both views are right, where does that leave us?

The problem at hand#section2

We can all agree that the realities of the web make it hard to build a standards-compliant site. Once the client’s CMS, outdated WYSIWYG editors, and third-party advertising code have finished with once-valid markup, things begin to look ever-so-ugly under the hood; this leads many to suggest, like Bowman, that an insistence on validation is at odds with commercial web design. Given that most of these invalid sites look fine in a browser, the amount of time and money required to produce perfectly valid final code seems not only prohibitive, but pointless.

Valid markup has become equated with two things nobody wants: impracticality and implausibility.

Refining the message#section3

If it weren’t for the early days of standards advocacy, for sites like the CSS Zen Garden, Wired News, or Fast Company, we wouldn’t be as far along as we currently are; heck, I’d probably still be a self-hating spacer.gif slinger. Despite those successes, our fractured take on validation stems partly from the wonderful evangelism that got us here.

Whenever I conduct a training session, I poll the room to see why the audience uses or plans to use web standards. The responses typically read like a doctrine that my generation of web designers have been raised on. Namely, that building with web standards can…

- shorten development cycles, as we no longer have to slog through through six layers of nested tables to build site templates.

- lower maintenance costs, as the CSS Zen Garden showed us.

- decrease page weight, which in turn reduces page load times and dramatically lowers bandwidth costs (we’ve Mike Davidson’s excellent ESPN.com interview to thank for those metrics).

These are, I think, the “sexier” benefits of web standards, the bulletpoints we’d use to sell prospective clients on CSS-/XHTML-driven designs. And with good reason: these are all excellent, compelling points. No sales pitch should leave home without ’em.

Noticeably absent from the list is any mention of why we should adopt standards, or what that process actually entails. I mean, I’m sure we can list benefits of producing valid code, such as:

- A proven increase in a site’s accessibility,

- The promise of device independence,

- The presence of a metric against which an individual or a team’s production can be measured, and

- The knowledge that your site is future-proof, displaying in any standards-compliant browser yet to be invented.

But the sum total of those points doesn’t exactly scream “compelling business case.” When you’re speaking to a mid-level marketing executive about standards, which would you rather lead with: saving terabytes of bandwidth, or investing in device independence?

Yeah. That’s what I did, too.

Yet while the benefits of valid code may not be glamorous, we can—and should—talk about them. Validation isn’t an end result or a final deliverable; it’s an ongoing process that continues long after a site launches. If we don’t put the proper tools and commitment in place, our work will start looking like a late ‘90s throwback, and if we don’t provide guidance and education on validation, the polished, perfect pages we produced will be snapped into software that’ll produce tag soup in seconds flat.

So how can we speak about validation in a way that’s compelling to our clients?

The hidden cost#section4

Validation might not have been the sexiest selling point for standards, but it does have very real fiscal benefits. In the past couple years of running my own practice, I’ve become slightly obsessive about tracking my time, especially when it’s spent dealing with bug reports. When an issue comes in, I note the error and the account, and start the timer. Once it’s resolved, I note the cause, stop the timer, and move on.

Toward the end of my first year in business, I noticed that more and more of my time was spent working around invalid code. Layout issues that would have been trivial to fix in a valid, error-free template would take significantly longer to debug in a live page that had a few hundred validation errors. It was a matter of figuring out which parts of the page weren’t causing the errors, so I could focus on fixing the problematic section. But when the page’s markup has three or four hundred validation errors, this process quickly becomes a time sink. A necessary one, but a sink nonetheless.

So by year’s end, I found that approximately fifteen percent of my time was spent mired in invalid code. As an independent designer/developer/something, I’m grateful for all the work my clients send me. Still, what if I was a salaried employee? If IT departments conducted a similar audit, I’m confident they’d find similar numbers. And this kind of auditing needs to happen. Invalid sites may look the same as those built on a foundation of valid, well-formed code, but in my experience, they invariably cost more to maintain. This is the silent weight of invalid code, a hidden cost we don’t discuss nearly enough.

Web two-point-next#section5

None of this changes the here and now. To be honest, the pragmatists are right: that for the most part, validation and commercial web design are polar opposites. But the tools are evolving to the point where we can begin moving beyond validation as a roadblock, and CMSes like WordPress and Slashcode are dedicated to producing standards-compliant code; visual editors such as Dreamweaver and (more recently) Microsoft Expression Web almost stubbornly refuse to produce invalid markup. So where do we go from here?

Pitch process, not code#section6

In recent months, I’ve been relearning how to sell standards. I still touch on the exciting bits (the lighter pages, the lower maintenance costs, and so on), but I don’t shy away from selling validation’s role in unlocking the real savings of web standards. And it’s been an easier sell than I’ve thought: once you’ve shown a client how standards can improve their sites’ accessibility, keep it future-proof and device independent, and lower maintenance costs, they’re usually ready to listen.

And that’s where the real conversation begins. By considering your client’s production workflow and the software that supports it, you and your client will be better able to identify what could break your joint commitment to standards—and as a result, they’ll be better able to fix these issues themselves.

Shop smart: shop standards#section7

Companies like Adobe and Microsoft have recognized the growing market for standards compliance, and openly tout their products’ W3C-friendliness in the sales material. But despite that silver lining, most CMS tools and online advertising companies are spewing out code that would make Netscape 3 proud.

This is where the lone consumer can move mountains. When meeting with a prospective vendor, our clients need to ask if the product is standards-compliant, much as they might ask if an ad serving solution provides targeting information, or if a CMS is J2EE compliant. Standards should be an equally weighted part of any decision-making process—and if we remind our clients of the financial benefits of validation, it will be.

Same sandbox, same struggles#section8

But in all honesty, the real work begins with us. Regardless of whether we find validation impractical or imperative, the infighting in the standards community is the biggest obstacle to real progress. Instead of trying to understand what factors make both sides agitated, we’ve vilified the people on the other side of the argument. We need to identify what’s making 100% validation so expensive and difficult, and work on removing those factors.

As our contribution to that effort, we’ll be discussing common validation killers and ways around them in an upcoming A List Apart article. You can contribute by using this article’s forum to bring up common obstacles to validation and the workarounds or process changes you’ve used to get past them.

Samuel Johnson once said, “Where there is no difficulty there is no praise.” Personally, I think that Sam would’ve sung a different tune three minutes into debugging his first CSS layout, but the man has a point: we can’t fall prey to complacency.

In a perfect world, clumsy software and bad workflows wouldn’t break our code, and validation would just happen. But until I also get that magical flying pony I asked for, we’ve got some work to do. After all, true standards compliance is only as impractical or implausible as we make it. Given how far we’ve come in the past few years, this next challenge seems like a trivial one indeed.

Let’s get to work.

There’s no question that browsers ought to be less permissive when it comes to sloppy, invalid markup. Otherwise, it’s almost “anything goes”. This is bad not only for accessibility, but perhaps more importantly, it hinders the growth and spread of awareness regarding the value of accessible and semantic code. It also encourages developers and companies to be lazy. We need greater awareness of what valid sytax is, how to make code more accessible, and education regarding semantic markup. We can either go for the lowest common denominator (which is the approach browsers have typically taken), or we can try to raise the standards and bring everyone along. As for validation itself, I just don’t buy the suggestion that validating can be too difficult or time-consuming. Developers — professional and unprofessional alike — don’t validate because they are either unaware of standards or they don’t care enough about them to bother.

bq. Go ask the people behind Google, Amazon, Ebay, MySpace (to name ONLY a FEW VERY WELL-KNOWN sites) why they are so incompetent, so unprofessional, so lacking in common sense. It should take them seconds to fix the problems, shouldn’t it?

I was talking from the perspective of building a new site, not fixing an existing one. Fixing tag soup is never going to be easy! These sites have clearly been designed without consideration for standards or validation, so trying to fix them will not be an easy job. But if you’re writing a website with the intention of making it validate, it really isn’t difficult to do.

The majority of errors on the Amazon homepage are unencoded ampersands, with the occasional non-SGML character, missing alt text or incorrectly nested tag. Unencoded ampersands should be easy enough to fix, and that will remove most of the errors.

bq. There’s no question that browsers ought to be less permissive when it comes to sloppy, invalid markup. Otherwise, it’s almost “anything goes”?.

um, Actually, I do question that reasoning.

I’ve noticed several posters have latched on to the idea that if we make standards into rules, then developers will have to follow them. Fortunately, an equal number of posters have countered with the observation that all computing is built on the legacy of someone else’s work. Simply put: enforce rules, and you break most of the Internet.

This is why standards are practical. In spirit, a democratic group of people got together, threw around some ideas, and agreed upon some educated guidelines. The more we exercise these guidelines, the more organized we’ll all be. But no one is going to force you.

In a reasonable world, the organized group with standards would have a bit of industry clout. And they do; browser makers heed standards when building new versions (some, better than others).

But (and this is just my thinking, here) standards hold very little clout with clients. They hold no brand name appeal, like “Web 2.0” or “Flash” or “AJAX.” Until they do, clients won’t start demanding them.

“Stephen”:#52 makes a good point about legacy code: pretty hard to standardize once things are already going.

The author anticipated this with a counter argument about how time gets eaten up, debugging code not written up to standards. This is true for spaghetti code, certainly, but I’m willing to bet places like Google and MySpace have a methodology in place.

Methodologies are also like standards: not rules, but guidelines. And, independent of standards, a group of professionals can follow a methodology _as if_ it were their “standard.” Capiche?

(Actually, I KNOW that MySpace uses a methodology: Fusebox. We use the same at my job. I’m the only guy on staff who’s a standardista, and yet we’re able to fix bugs lickety-split.

Of course, I make less of them, in the first place…)

There are a number of issues at odds here. In my case, in the company I work for, the problem now is not convincing the business of the benefit of developing to web standards, it is actually educating some of the people who work in the web department here how to use them effectively. It is very easy to produce technically valid code that is just as nasty in a tag soup kind of way as any of the ‘old’ table-based websites we have all grown to scorn so much.

The problem with this is that there are a number of developers from the ‘old school’ who haven’t taken on the principles behind all this standards compliance madness that has been sweeping the web over the past couple of years. Their mentality is still stuck in the ‘structural’ rather than ‘semantic’. They dont yet really grasp that if you span everything up, and produce a million and one styles needlessly, you really dont have many of the benefits that the standards compliant web should offer. Development time and bugfixing time remain high, and page weight is just as high (if not actually higher, as was the case with a major project I took on a total code re-write for a few months ago).

One of the other things I seem to hear and read a lot these days is that web browsers should be less tolerant of poorly written code. To me, this attitude, although it may make our lives easier, is wholly against the spirit of the internet. Forcing anyone who wants to put together a web page to learn (for many, quite complicated) code languages would prove such a barrier to so many people that they would be much less inclined to use the internet to publish their views, interests, loves, hates etc etc etc. Admittedly, this situation is subsiding as so many people just use a simple blogging engine, but what about the kids that are just starting out,… Who have an interest, but only have a (fairly bad) WYSIWYG editor? I started out like that, years ago… And now I’m here as a web professional – The authority in a very, very large business on how we should be developing our platforms to web standards etc. Also, you would completely break much of the old content out there. Some of you would say that it shouldnt be there in the first place… But the people who made that content might love it, and I for one don’t want to take that away from them.

As for my employers? Like I said, selling web standards to them isn’t a problem any more. In fact, much of the time I wish they would pay less attention to the buzz and trends on the internet. They have all gone mad for ‘Web 2.ohmygod’… They want to jump on this ‘cool’ bandwagon. We even have links to add our pages to del.icio.us and google bookmarks, for god’s sake! Let me make this clear, here… We are NOT a cool company!

I like web standards. They make my life… Interesting. Internet Explorer makes my life with web standards somewhat more painful… But I can live with that. I think MY next step will be to sell web standards, and more specifically their proper use, to many of my colleagues. Its going to be a hard sell… They have been doing this for longer than I have, and that, in large, is the problem.

I can claim a win for valid code.

I persuaded a wagering company (bookmakers mainly, casino, poker as well) to use valid XHTML 1.0 Trans and CSS2 on their wagering (e-commerce) sites. We made the case on fast downloads (they value customer service), SEO (they have restrictions on advertising in most countries they operate in), quicker issue resolution, forward compatibility, use of javascript (valid DOM), easier for the marketing team to produce creative for the sites (there are currently 5 sites in the stable, all running variations of the code), ability to roll-out more websites with different brands (about 70% of the CSS is common to all sites and the rest is brand specific).

I had to go in and hand-code every single screen of the web apps, four days a week for six months; then hand-hold the IT department through integration into their ASP.NET web applications (they grumbled every time I didn’t let them use a library control). But it all works and it delivered for the end user. The sites now turn-over almost 1 billion dollars (AU) per year and we’re brought in as a team to deliver enhancements and minor maintenance.

It’s now a battle to keep it all clean with the .NET developers still under pressure to roll out library controls every week; but the sites are still largely valid and standards compliant.

This business is completely results focuseed and they are very happy with the work we did; so I reckon anyone can be persuaded to implement the basics; just be prepared for the client-side code to depart from standards and need herding back every month.

I congratulate on really great piece of writing.

I agree with Lasse, that SEO sells. Thus it is possible to force client to have semantic website as this plays a part in the overall optimization.

I generally find that most clients who want a website don’t think of it in code. They look at it visually and naturally hire a graphic designer to mock something up for them in Photoshop before hiring the web developer to “code it.”

A big mistake is for clients to make “coding” a page the LAST step. Often this will lead to shortcuts and hacks in the markup and CSS, cross-browser incompatibilities, and if working in a team; the worst scenario of all — a mish-mash hodge-podge of markup. It can truly ruin a project and makes standards-compliance a sick joke.

As an aside, another barrier I’ve found is the team itself. If there is more than one developer working on the markup you most often get one of two extremes: either the team gels and conforms to sets of conventions and markup style or they play by themselves and mix up their styles and hacks. Communication is key and requires that designers agree to standard ways of implementing the standards. When it works, it’s gravy — but most people groan when someone suggests introducing more process. Some people feel they are more productive in the “cowboy coding” method.

In the past I’ve found that I’ve been most successful when I was the sole developer and designer. I was mostly happy when I was the developer working with a designer that understood (mostly) CSS and web design. I was mostly unhappy when having to hack a graphic designer’s PSD into a use-able design. And I was miserable when I had to hack designs out over and entire site and various applications in a team using various CMS’s and templating systems.

Is it impossible? No — but it does require a certain level of organization and discipline in the process to work.

It’s actually the “anything goes” philosophy that has made the Web so powerful. Standards are great, but if browsers became less permissive, it would as someone else pointed out, break the web. I think that regulation would be the worst thing to happen to the web and internet. It was created as a medium of open expression and if we started telling people they had to follow set “rules” I think we would lose that freedom. I think businesses and web development teams need to establish best practices and enforce standards, but it’s not contingent upon anyone but them to enact these standards.

As the web grows, and users of the web move from PC’s and web browsers to mobile devices and even things like appliances in the kitchen, the need for standards and accessibility will increase, and eventually the new will suplant the old. There will be no need for regulation. The web (the USERS of the web) will regulate itself over time.

I guess the answer is DocTypes…

Quirksmode can still be the sandbox for starters. And regulations could enforce professional website builders to use only certain DocTypes upon which browsers act less permissive.

Look, most browsers already follow certain rules and standards. That’s why many tags work as we expect them to, and basically compel us to code in certain ways. If they didn’t, then why have tags at all? Why even have a language like (X)HTML at all (which is also based on rules and practices)? Asking for browsers to be a bit more strict is not the same as calling for “regulation” by some unseen government. And I don’t think it will “break the web” either. The other implication of what I read from some posters goes something like this: “let’s not bother trying to educate people who are probably incapable of understanding html or how to make web pages that will reach the broadest possible audience. Let’s just keep everyone at the lowest common denominator of knowledge and skill. And don’t bother informing and educating people about how to make their pages more accessible, or that making pages with certain programs or methods will leave these pages inaccessible to readers who rely on assistive devices.” What kind of freedom are we talking about? This reminds me a bit of Rousseau — we may need to give up some of our ‘natural’ liberty (no rules at all, a state of nature) in order to achieve a form of ‘civil’ liberty on the web — which is a form of association and yes, in some sense, a social order.

@54: You mean fusebox.org where the use of whitespace before the doctype declaration ensures that IE will bounce into Quirks mode even though it is declared as XHTML1.0 Strict (no, there’s 24 errors, so it isn’t)?

As for Google, I just don’t understand how such a simple home page can have 30 errors on it (.co.uk) and that they can’t be bothered in their 20% of hacking time to just fix the bloody thing. Even slightly. The fact that the page still works is more luck (and browsers accepting all kinds of crap) than judgement.

Send Google’s website through the W3C validator. Look at the number and kind of errors you get. Remember that this is probably the one most visited website in the world, made by some of the top professionals in the field, aiming at the highest possible crossbrowser compatibility and user accessibility.

Only a few months back I was constantly exhausted and approaching a serious depression. I wanted to be at the forefront of technology. I felt proud. I made every webpage I designed to validate as XHTML strict. All websites looked just supercool in Firefox, but shitty in at least a quarter of the browsers used by my visitors. I did not sleep much, because I tried to meet deadlines and still vertically center some liquid CSS tag-soup in IE 5 Mac. I often cried and hated to be alive for the first time since leaving puberty.

Until I looked a Google’s sourcecode and realized that I had been wasting my life over nothing.

XHTML and CSS were developed by folks who frequent text only websites. LOOK at the sites these guys output! I do graphics. Now I again do what works best. I use a mixture of tables layout and CSS today. Some of my code still validates. I sleep well. My sites look just perfect in all browsers (even Lynx).

If you think about this, you will easily understand why the movement to propagate web standards failed. Because no-one will give up eating with his fingers for a blunt knife and flat spoon.

You can validate font tags, unquoted attributes, unsemantic markup and bold tags instead of proper headings